[Research] “Gotta Detect 'Em All: Fake Base Station and Multi-Step Attack Detection in Cellular Networks” Paper Review (EN)

Hello! I’m clalxk.

It’s been a busy year-end (two schools…), so I’m back with a paper review… haha.

In this post, I’ll review a paper that detects Fake Base Stations (FBS)—a threat that remains very realistic in cellular networks—and the Multi-Step Attacks (MSA) that are launched using them as a foothold, from the User Equipment (UE) side. This paper was presented at USENIX Security 2025A (link).

The paper proposes FBSDetector, an ML-based detection framework, and describes an ML-based detection solution that leverages Layer-3 network traces on the UE (User Equipment) to respond to the severe security threats posed by FBS and multi-step attacks (MSA). Based on the first large-scale, high-quality FBSAD and MSAD datasets built to reflect realistic scenarios via POWDER, the solution integrates stateful LSTM with attention for FBS detection and graph learning for MSA recognition. FBSDetector achieves 96% accuracy with a 2.96% false positive rate for FBS, and 86% accuracy with a 3.28% false positive rate for MSA, and was deployed as a mobile app and validated in real-world settings with low overhead.

Background

Among cellular network attacks, the reason FBS (illegal/rogue base stations) are scary is simple. By pretending to be a legitimate base station (impersonation), an attacker can lure the UE, and then mix in various attacks (DoS, downgrade, location tracking, etc.) so that they look like normal “protocol procedures.”

The threat posed by FBS is not new and has existed for a long time, but it is still widely used by attackers around the world.

- Standard/spec-level defenses are slow: It takes a long time for a new defense to be incorporated into standards and propagate to chipsets/devices/networks.

- There are already too many vulnerable devices worldwide: Replacing them is not realistic.

- Limitations of existing detection

- Heuristic/signature-based approaches are weak against adaptive attackers (slightly tweaking fields or changing the order…?).

- Crowdsourcing/external hardware dependence is hard to deploy at scale or is costly.

- Approaches that only look at lower layers (physical/wireless) struggle to cover sophisticated FBS and MSA.

The paper goes one step further and emphasizes that it’s hard to conclude “it’s safe because it’s 5G.” While IMSIs were used unencrypted in 4G, there is still room for FBS to be used for attacks in 5G, and recently proposed certificate/signature-based defenses introduce not only overhead and spec changes, but also key-sharing issues in roaming environments.

It also argues that while Google/Apple have adopted new approaches to neutralize FBS, outside that scope, knowledgeable attackers with equipment can still operate—so detection itself is necessary.

Therefore, this paper heads toward: “Then, using only the Layer-3 traces (NAS/RRC) that the UE already sees, let’s catch this on-device at low cost.”

NAS: control-plane protocol between UE ↔ core (EPC)

RRC: control-plane protocol between UE ↔ base station (eNodeB)

MSA: an attack that uses FBS as a foothold and chains multiple procedures/messages to achieve an end goal (DoS/tracking/downgrade, etc.)

Methodology

0. System Overview

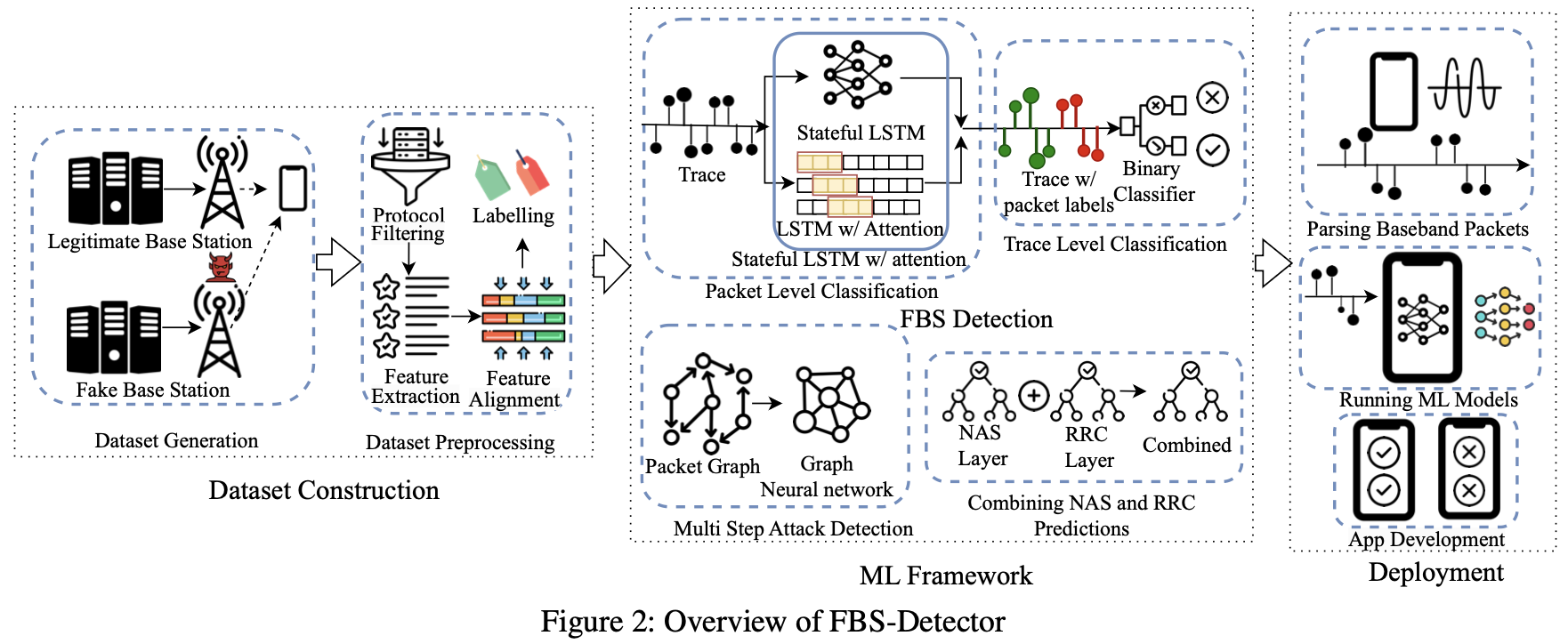

The overall flow is: “(1) build the dataset → (2) two-stage FBS detection → (3) graph-based MSA recognition → (4) fuse NAS/RRC predictions → (5) deploy as an app.”

Figure 2: FBSDetector overall architecture

Figure 2: Overview of FBSDetector, including dataset construction / ML framework / deployment

1. Threat Model & Scope

The attacker model assumed in the paper can be summarized as follows.

- Impersonate a legitimate BS and induce UE reselection with a stronger signal

- Learn/imitate legitimate values by eavesdropping on public channels

- Not at the level of breaking crypto itself or physically tampering with the SIM/core/BS equipment

- But can try to evade detection via rapid parameter changes, transmit power control, obfuscation, etc.

The deployment scope focuses on 4G (LTE). The reasons are (1) 4G is still widely deployed in practice, and (2) the experimental infrastructure (POWDER) needed to build the dataset supports 4G experiments well.

The paper’s “design challenges” can be summarized into the following five items.

- Dataset availability/quality (C1): It is hard to obtain realistic data that includes legitimate BS/FBS/MSA.

- FBS detection from packet traces (C2): The same message can be benign/malicious depending on context.

- MSA recognition (C3): Multi-step patterns are complex and evolve.

- NAS/RRC prediction fusion (C4): How to combine layer-specific models into a single decision.

- Real-time detection (C5): Must enable fast capture/processing/inference on-device.

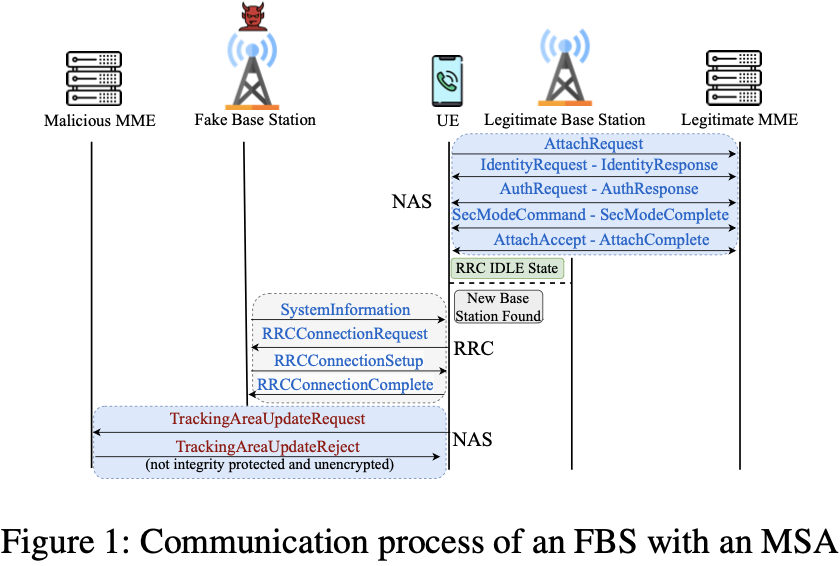

2. TAU Reject (FBS-based MSA)

One representative attack described in the paper is TAU Reject. It may look like a “procedure message,” but in practice it can drive the UE into an out-of-service state or trigger downgrades, etc.

The key points are:

- The FBS lures the UE using a strong signal and reselection priority.

- To make the UE appear to have detected a new TA, the FBS operates with a different TAC.

- When the UE requests a TAU, the FBS sends a TrackingAreaUpdateReject to achieve the goal.

Figure 1: TAU Reject attack flow

Figure 1: TAU Reject flow (lure UE to FBS → inject Reject during TAU procedure → impact connectivity/service)

3. Dataset: FBSAD / MSAD (POWDER-based)

One strength of this paper is that it constructs the dataset to be close to real-world conditions. Because running FBS experiments in public places is illegal, the paper builds the dataset on the POWDER testbed based on real over-the-air (OTA) packets.

- FBSAD: for FBS detection

- MSAD: for recognizing 21 MSAs

- Total 9.2GB (raw), including mobility and attacker capability levels (0–4)

The attacker capability levels are also quite detailed.

- Level 0: “Simple operation with high signal strength”

- Level 1: “Signal strength tuned to be ideal for inducing handover/reselection”

- Level 2: Replicate legitimate BS parameters (cell ID, MCC/MNC, TAC, PCI, RF parameters, SSB/TA, etc.)

- Level 3: Perform common MSAs based on Level 2

- Level 4: Adaptive reconfiguration for evasion, such as field changes / time-order changes

3-1. Data generation (What did they do on POWDER?)

On POWDER, the paper constructs a cellular network that integrates legitimate BS/FBS and MSA, and collects traces by capturing packets at all cellular network components. It also clearly explains why mobility (UE moving and handovers occurring) is included in the dataset: without it, normal handovers could be misclassified as malicious.

From an implementation standpoint, they use Open5GS for the core network, and both srsRAN and OpenAirInterface (OAI) for the UE/BS stack to reduce bias toward a specific implementation.

3-2. Preprocessing (protocol filtering & features)

Since each packet in the trace contains multiple protocol layers, the paper performs protocol filtering to keep only NAS/RRC, and then extracts relevant field values.

- NAS layer: 119 fields

- RRC layer: 183 fields

These fields are used as input features for model training.

3-3. Labeling (benign/malicious, and attack types)

Labeling is done based on “why was this packet generated?”

- FBSAD (binary label): 0 for benign packets, 1 for packets generated by the FBS

- MSAD (multi-class label): 0 for benign packets, and packets generated by attack (

attack_j) are labeled asLA[attack_j]

Because there are fewer NAS packets, they manually labeled them by inspecting each packet (the paper says it was a one-time effort of about ~2 hours). For RRC packets, they detect the attack interval from NAS traces and then batch-label them with an automated script based on that interval.

4. FBS detection: two-stage (packet → trace)

A nice intuition in the paper is reflecting the idea that rather than a packet itself being malicious, often it’s the context in which the packet appears (preceding/following context / sequence) that is malicious.

So FBS detection proceeds in two stages.

- Packet-level classification

- Classify each packet as benign/suspicious

- Predict using a combined Stateful LSTM + Attention structure in parallel

- Trace-level classification

- Decide “is this trace an FBS session?” based on packet sequence order/patterns

- Avoid a naive heuristic where a single malicious packet flags the entire trace

To add a bit more detail: for packet-level modeling, stateful LSTM preserves long-term dependencies by maintaining state across batches, and attention learns to place higher weight on decisive parts of the sequence. The two outputs are extracted in parallel and combined (concat/merge), then the final class is predicted through dense layers.

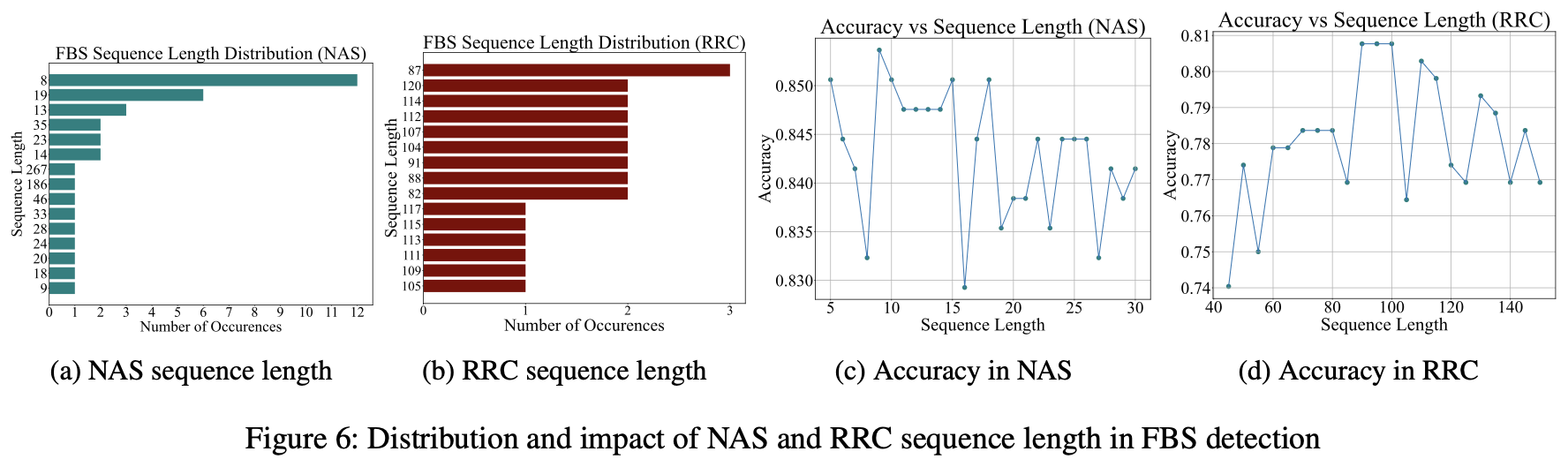

In particular, the analysis showing performance changes depending on sequence length was interesting (and it’s also a part people often struggle with when tuning models).

Figure 6: Sequence length distribution and performance

Figure 6: Trend that performance improves around sequence lengths 9–15 for NAS and 80–120 for RRC

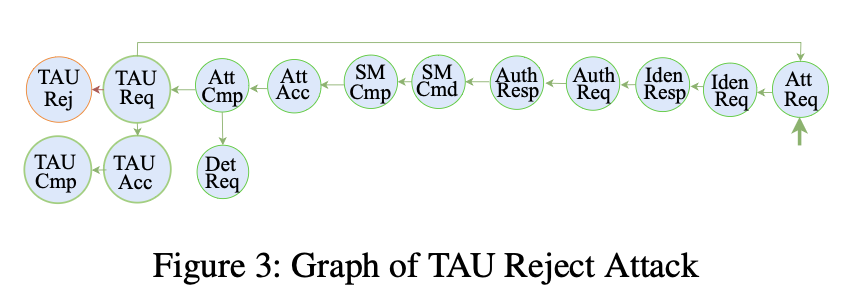

5. MSA recognition: learning “patterns” with graphs

MSA is not just “a few messages”; it is closer to a pattern of chained procedures. The paper represents this as a graph.

- Nodes: unique values of message types (e.g., NAS:

nas_eps_nas_msg_emm_type_value, RRC:lterrc_c1_showname) - Edges: transitions to the next message (directed), and labels for whether the transition is benign/attack

Among the evaluated graph models, GraphSAGE performed best, so they use it.

Figure 3: Example graph representation for MSA detection

Figure 3 shows that attacks such as TAU Reject appear as “path patterns,” and the system learns these patterns to recognize MSA. For the “what if the attack evolves?” problem, the paper proposes a direction that leverages ideas like maximum common subgraphs, using the intuition that it’s often not a completely new path, but partially overlapping.

The paper also explains this more formally. If a packet-derived graph is represented as (G=(V,E)), known attacks appear as specific paths (P(G)) in the graph, and evolved/reconfigured attacks may appear as different paths (P’(G)). However, due to vulnerability/procedure characteristics, it is likely that these paths are not completely disjoint and may partially overlap. The intuition is to leverage this “overlap” to detect unknown attacks.

6. NAS/RRC prediction fusion (weight-based fusion)

Because NAS and RRC have different characteristics, the models are trained separately and then their predictions are fused at the end using a weight-based method. (The paper mentions Dempster–Shafer theory and explains it as assigning higher weight to the more reliable side.)

Experimentally, fusing NAS+RRC predictions improved performance by about 1–2%.

7. Deployment: distributing as a mobile app

Rather than stopping at experiments, they deployed it as an app and measured overhead.

- MobileInsight: baseband trace parsing

- TensorFlow Lite: on-device inference

- Flutter: app UI

They also mention practical barriers such as rooting requirements. Additionally, assuming real deployment, they anticipate an operational model where models are periodically retrained to reflect new attacks and quickly deployed via app updates. Since NAS/RRC traces can be sensitive, they also note that data collection should be enabled based on user consent.

Performance Analysis

To summarize the key results first:

- FBS detection: 96% accuracy, 2.96% FPR

- MSA recognition (21 types): 86% accuracy, 3.28% FPR

- 1–2% improvement from NAS/RRC fusion

- Reported 86% zero-shot detection accuracy for overshadowing attacks

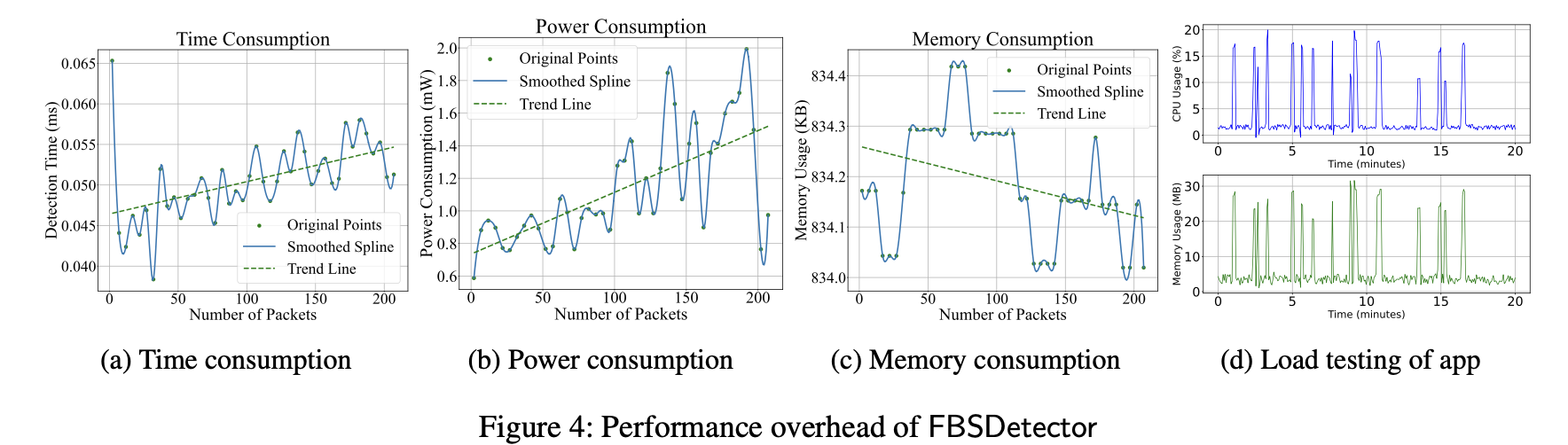

The following figure is the core of the overhead analysis.

Figure 4: Overhead analysis

Figure 4: Time/power/memory usage increases linearly with packet count, but with a small slope, suggesting practical usability

The paper also presents quantitative numbers: on average it runs at about 835KB memory and <2mW power, which is relatively low compared to prior approaches (~4mW).

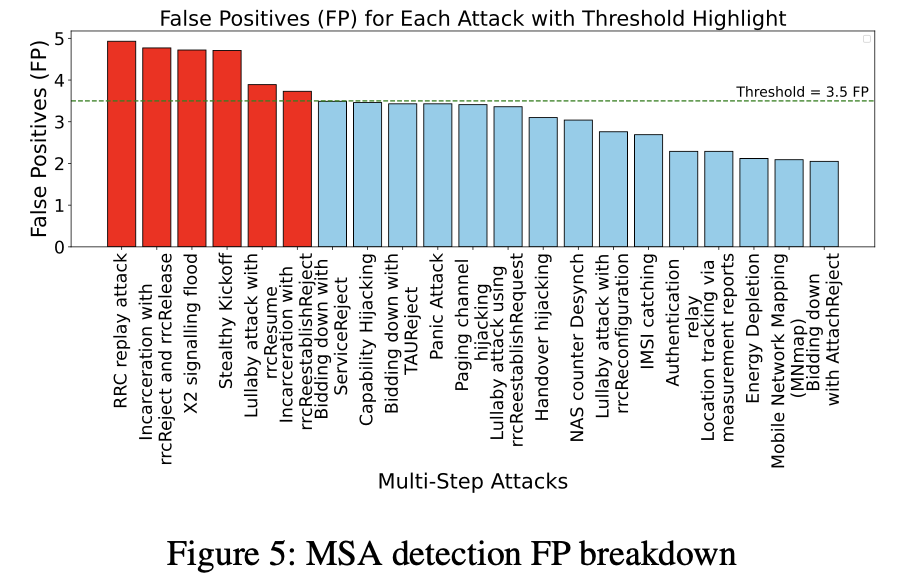

They also show that certain attack types contribute more heavily to false positives in MSA (cases that are almost indistinguishable from benign behavior from the UE’s perspective), and provide an analysis figure.

Figure 5: False positive analysis for MSA detection

Figure 5: Certain attack types contribute heavily to FP → the root cause is that they “look the same as benign behavior from the UE’s perspective”

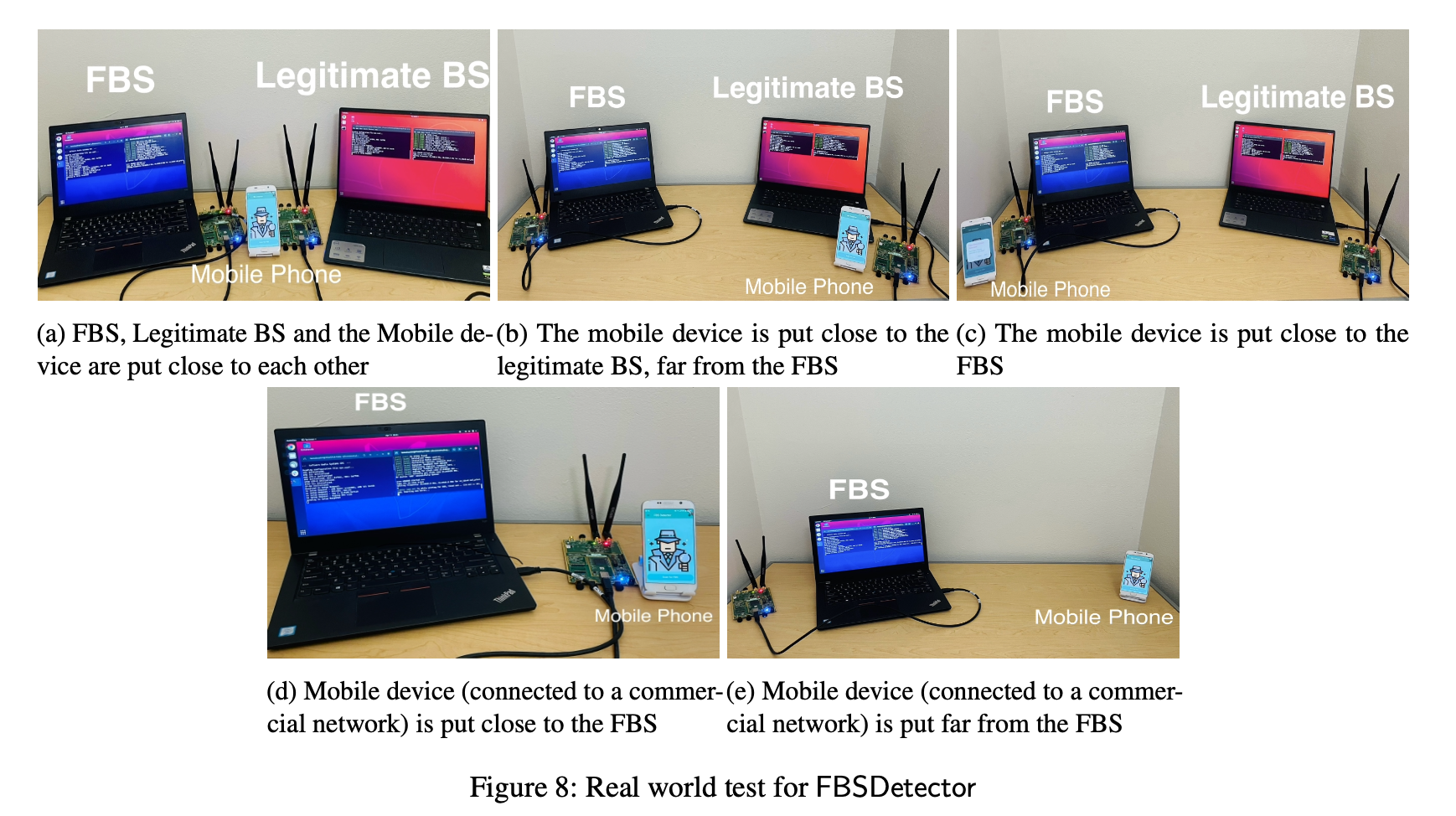

They also performed fairly rigorous app validation in a controlled lab environment.

Figure 8: Controlled lab environment setup

Figure 8: Controlled experiments with USRP B210, a laptop (core), and a smartphone (app)

The experimental scenarios include a lab 4G network with their own SIM, commercial SIMs (e.g., Google Fi), distance changes, and limited mobility. In the 24-hour stress test, they executed 21 attacks 5 times each, for a total of 105 attacks. In the long-term test, they ran the app for 7 days under various usage patterns and observed environments where packets accumulate.

They also ran comparative experiments against existing app-based detection solutions (AIMSICD, SnoopSnitch). In the same controlled environment, those two solutions did not detect the FBS, but FBSDetector did (as described in the paper).

Conclusion

In one sentence, FBSDetector can be seen as a “UE-side detection framework” with the following direction.

- Using only Layer-3 (NAS/RRC) traces

- On the UE (device)

- Performing FBS detection + MSA recognition

- As a practical framework with relatively low overhead

In other words, FBSDetector is an ML-based FBS/MSA detection system that uses Layer-3 network traces. It builds large-scale realistic datasets (FBSAD, MSAD) and achieves high detection accuracy with low overhead by using advanced ML models such as Stateful LSTM with Attention and Graph Learning. The paper states that future work will port FBSDetector to 5G networks, support detection of overshadow attacks, and focus on integrating FBS detection and attack defense mechanisms in ORAN environments. I’m looking forward to seeing how it expands both the porting process to 5G and the detectable scope.

Closing thoughts

Personally, beyond FBS detection itself, I found the attempt to model MSA as graphs and learn them as patterns especially interesting.

Of course, the limitations are also clear.

- Rooting/permissions/device constraints (especially on iOS) remain major barriers to deployment.

- Attacks that “look identical to normal behavior” from the UE’s perspective are inherently difficult (FP/FN).

- Expanding to 5G/other environments brings back the experimental infrastructure and dataset problems.

One particularly impressive part (in the translated version) was how realistically the paper discusses “what FP/FN mean.” Since FBS itself is not a frequent event, even a small FP rate can significantly degrade usability in real deployment. With that in mind, the paper leaves room to interpret that at the current stage, it may be especially useful in security-first environments or for sensitive user groups rather than the general public.

Still, it was a very interesting read. If I find another interesting paper on cellular networks, I’ll be back with another review~~

본 글은 CC BY-SA 4.0 라이선스로 배포됩니다. 공유 또는 변경 시 반드시 출처를 남겨주시기 바랍니다.